By Helen Turnbull

A very happy new year to our friends across the globe! As 2019 begins to unfold its surprises, I was reflecting on the familiar saying ‘out with the old and in with the new’ that marks the beginning of the next twelve months. I agree with the saying ‘in with the new’ from the perspective of technology, particularly in the fast-paced world we live in today, but in terms of scientific research, it is the old that is vital as a foundation to the new. We are discovering more all the time about leopards and their behaviour, and believe it or not, there is still a lot to learn about these fascinating felines.

As CEO of the organisation, it is a rare privilege for me to be able to spend time out in the field with those at the coalface of our research work, and certainly, my new year’s resolution is to do more of it, time permitting. I found it inspiring and interesting to support the processes that led to the successful conclusion of a year-long camera survey in the Cederberg. From start to finish it took two years to complete if we take into consideration the time it took to identify the areas to be covered; the long and difficult recces across spectacular landscapes to see where leopards would most likely roam, and deciding on the right cameras as well as how to protect them. All things considered, it is a significant physical and emotional investment. The deployment process required kilometres of hiking each day into remote areas, carrying all the necessary equipment. Cameras must ideally be placed as paired stations, and sometimes it requires that the surrounding bush receive a bit of a trim, just to reduce the risk of false triggers. It’s a specialised task to set the cameras up properly and make sure they operate at their optimum. Once set, there follows a bi-monthly servicing cycle to download the images and change batteries in 146 cameras over 150,000 hectares.

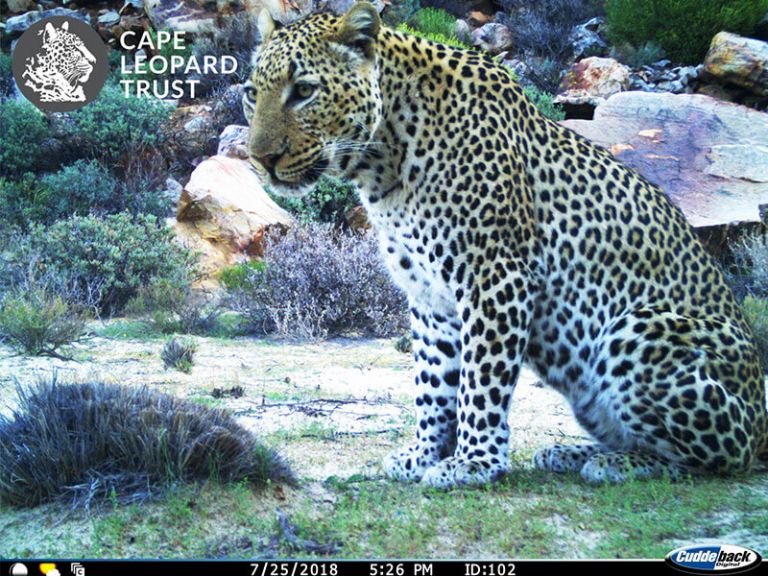

It is thanks to the hardy Cederberg team, and the advanced camera technology, that after many months of backbreaking work, the total survey identified more than 60 individual leopards, some known to us from a previous Cederberg survey back in 2010. It is awesome to see the detailed photographic records of these enigmatic cats, which gives us a rare glimpse into the secret lives of these elusive predators.

For this, we are grateful to one of the most diverse tools in conservation today – the remote-sensing field camera or camera trap for short. Especially when working with a cat that is so hard to find, the camera trap is invaluable. Today’s units are even more advanced than just a few years back and provide us with invaluable information to be processed and written up in research papers, to improve knowledge and guide future predator conservation. The cameras are our spies on the ground, equivalent to a team of invisible workers able to see things that we are not. Many people ask to come and visit our project, full of excitement to see a leopard in the wild or ask if we can bring a leopard to them for a visit so they can help raise funds for our work. It’s simply not as easy as that. As exciting as this prospect is, the leopards of the Cape are completely wild and known as the ‘ghost cats’ of the mountains for good reason.

Some people question if these mythical creatures really exist in the Cape mountains, and it is a testament to the amazing adaptability and versatility of leopards that enables them to survive against all odds, often in extreme conditions. The stark reality is that many in our team are still waiting for their leopard ‘aha’ moment. And, as we declare the New Year open for business, filled with new possibilities, we celebrate the leopards of the Cape, and the wonder and magic they invoke when they occasionally do reveal themselves. With this in mind, I would like to introduce you to Justin Fox’s book ‘The Impossible Five’. Justin is a renowned author and editor of Getaway magazine. An enthusiastic travel journalist, he made it his mission to go in search of the top five of South Africa’s most elusive mammals to create the book. In this short extract from ‘The Unspotted Leopard’ he gives his personal account of an experience in the Cederberg looking for a Cape leopard with Dr Quinton Martins:

As for us, our journey and efforts continue to protect the Cape’s magnificent leopards, knowing that they are probably watching us much more than we see them! It’s into the fray once more, using our knowledge, scientific research and education to make a difference, thanks to our amazing partners and friends. We couldn’t do it without you, and we wish you all ‘Tswalu’ (new beginnings).

Extract from The Impossible Five by Justin Fox

On my last day in the mountains, Quinton and Elizabeth arrived to take me on a concerted hunt for Spot, the female that frequented our area. It was a final roll of the dice.

Driving up Uilsgat Kloof, we picked up a strong telemetry signal. She was definitely in the valley. But where? Her echo bounced off the rocky walls, making accurate bearings difficult. We parked and got out.

‘I’m getting a fairly good signal from the other side of the kloof, half way up Mied se Berg,’ said Quinton. ‘You okay for a bit of a hike?’

‘Sure,’ I said unconvincingly. By now, I knew what ‘a bit of a hike’ meant.

As we prepared our packs with water, food, cameras, binoculars and telemetry equipment, Elizabeth glanced at the cliff and exclaimed: ‘Look at those black eagles! They’re attacking something!’

‘My God, I’ll bet you it’s Spot,’ said Quinton, grabbing his binoculars.

We watched the two great birds making an attack run. They approached in a parabolic swoop, then folded their wings and dropped out of the sky in a near-vertical dive. As they plummeted, each bird let out a scream that raised the hairs on the back of my neck. The Stuka dive-bombers of the berg. At the last moment, when it seemed inevitable they’d smash themselves against the cliff in an explosion of feathers, the birds flared their enormous wings, talons extended, almost brushing the rock as they soared back into the blue.

‘There, on that big boulder, she’s cowering!’ shouted Quinton.

I trained my binoculars in the direction he was pointing. Nothing. Or perhaps a glimpse of movement?

‘Where exactly?’ I asked. ‘The big round rock, above the diagonal one.’ I looked again, willing the leopard to show itself. Which round rock, which diagonal one? They were all round or diagonal. There! Had I seen something? Maybe just the hint of a cat, a vague feline suggestion? Maybe not.

‘She must have slipped behind the rock,’ said Quinton. ‘Let’s move. Fast. If we angle to the left, we can herd her up the valley towards our traps and maybe get a sighting into the bargain.’

‘Herding cats,’ I muttered under my breath as we set off across the valley floor at an unsustainable pace. Quinton and Elizabeth took giraffe strides; mine was more suburban. We came to a stream and my two companions stepped over it without breaking stride. I sloshed through, filling my shoes with mud. By now, every animal in the valley knew about Spot, and the alarm calls of a grey rhebok ahead of us were picked up by a troop of baboons. The kloof was a natural amphitheatre, and the sounds echoed around us, backed by a chorus of birdsong. I was thrilled. It was just like being David Attenborough in the climactic scene of a BBC doccie.

We scaled the western slope and veered along a contour towards the likely boulder. My two companions had changed from giraffes to klipspringers, their cloven hoofs gripping the rocks as they gambolled ahead. I slipped, grazing a knee. The telemetry, pinging like sonar, told us Spot hadn’t moved far, and Quinton motioned us to continue in complete silence.

We came to an outcrop, took off our packs and scrambled up to a ledge. My shoe sent a pebble clip-clopping down the valley. Quinton looked back at me with a severe frown. Poking our heads over the lip, we scanned the area where Spot should have been. The telemetry told us she was less than fifty metres away, but we just couldn’t see her. The dassies on a nearby boulder were going ballistic with their alarm calls. They’d certainly seen her. All we could do was wait for Spot to show herself.

This waiting and staring and telemetry and looking at each other with quizzical looks went on for about twenty minutes. Then Quinton edged off to the left and we followed, trying not to dislodge any more stones or breathe too loudly.

‘She’s on the move,’ whispered Quinton. ‘You two wait here. I’ll try to flush her out.’

He scrambled down the rock face, angling to the right to force her up the valley into open ground. His telemetry aerial swung back and forth above his head, making him look like Robotman. We scanned the scrub, triangulating our gaze with the direction of Quinton’s aerial. How could a big cat vanish into such meagre cover, right under our noses, and wearing a telemetry collar to boot?

After half an hour, Quinton returned, looking dejected. We found some shade and ate our sandwiches. ‘As you can see, this is a very, very frustrating game,’ he said, staring across the valley to where the baboon troop barked lustily, marking Spot’s progress somewhere along the opposite slope.

My time was up. I drove out of the enchanted valley, over Uitkyk Pass, and down the winding gravel road to Algeria. My thoughts turned to how, up there in the mountains, the future of leopards was relatively secure. For now, at least. The region had once endured the greatest predator-farmer conflict in the Cape, with up to seventeen leopards killed annually. But in 2007, an area of 1 710 square kilometres had been set aside as the Cederberg Conservancy. With Quinton’s help, the entire farming community had agreed to ban gin traps. Livestock farming with sheep, goats and cattle had then been the predominant land use; now wine production, olive trees and citrus predominated. Leopards are not vegetarians ... and they’re teetotallers.

And what of Spot? Had I seen her, or hadn’t I? My imagination certainly produced a vision of sorts. Spot was there on the rock, bathed in sunshine, her back arched. She stared up at the reat bird falling towards her. Her whiskers bristled as she bared her fangs. Those golden eyes, their pupils narrowed to tiny slits, measured the approach of the eagle, readying herself to strike. A flicking tail, claws anchoring her to the rock, a sinuous body pressed low. I could even hear the soft growl coming from deep inside her, like the sound of distant thunder.

Had I really seen her? Quinton certainly had. Elizabeth might have caught a glimpse. I was less sure. Did the fact that one person in the group achieved a sighting mean that, technically, the group as a whole had seen a leopard? Are one’s own pair of flawed, short-sighted eyes that important in the bigger scheme of ‘the sighting’?

And maybe I had, actually, seen a fleeting shape. A half-sighting or perhaps a ‘sort of’ sighting. Did a half-sighting count as a sighting? If one rounded up the half to a whole, which even the most fastidious accountants permit, then I’d definitely spotted Spot. I had seen a Cape mountain leopard! Sort of.