Every weekday morning in Cape Town more than two million people begin their daily routine. The freeways that surround the slopes of the mountain are clogged with traffic. As commuters head to work they are probably oblivious to the close proximity of a predator.

A caracal stands on the side of the four-lane M3 highway. It’s a young adult male and while the city’s been sleeping, he’s spent the night in the suburbs, looking for new territory and hunting rodents. Now he’s trying to run the gauntlet of speeding cars and get back to the sanctuary of Table Mountain National Park. He takes a chance and dashes across, but although caracals are one of the most elusive of wild cats, even he can’t dodge the stream of vehicles. A car hits him and his skull and hindquarters are fractured, causing instant death.

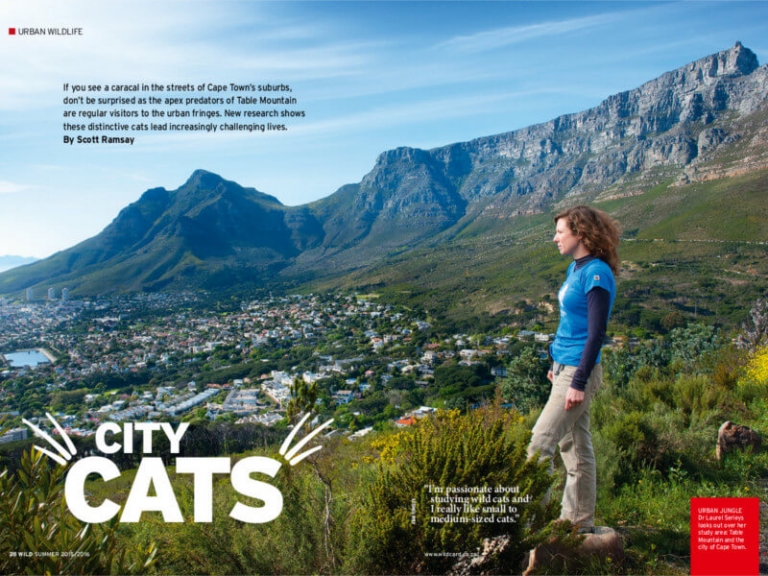

This is the story of Jasper, a caracal fitted with a GPS-enabled radio collar by American researcher Laurel Serieys. It’s also the story of Savannah, a young female caracal killed by a car three weeks after she had been collared.

“Vehicle collision is probably the most common cause of mortality on the mountain,” the 35-year-old Texan explained. Since November last year, Laurel has collected nine carcasses of caracals that have been hit by cars, some in the city, others along the West Coast and in the northern suburbs of Cape Town. “There are probably many more that are hit. We will only ever know if people report the incidents.”

Jasper was a bit of a local celebrity and he became a hot topic of discussion on a talk-radio station when people called in to report his presence. Laurel believes Jasper was regularly exploring the suburbs because he was looking for new territory. The GPS data from the radio collars suggests that young male caracals may be more susceptible to road deaths, because they’re usually the ones on the urban fringes. Older males seem to spend less time in close proximity to urban areas than the young males pushed to the edges.

The Urban Caracal Project has more than 2 600 people following its Facebook page, and more than 100 000 people regularly view the photos and videos that Laurel posts online. Capetonians are increasingly sharing their sightings of caracals. When Jasper was hit by a car, five people called Laurel to notify her of his death, including the distraught driver.

Laurel spends almost all of every day hiking up and down the mountain, mostly checking traps that she has set to capture the caracals, so she can put GPS radio- collars on them. She uses safe and humane cages with a variety of visual and scent lures to entice the caracals inside. Each cage has a transmitter that sends a radio signal notifying her when an animal is trapped inside.

Even so, Laurel checks every trap herself at least four times a day. Usually she finds small grey mongoose, large-spotted genetor porcupines, which she lets go.

On rewarding, rare occasions, she may see the distinctive long-tufted ears of a caracal. Then she’ll immediately call a veterinarian who supervises the drugging of the caracals to dart the cat so she can fit a radio-collar, which weighs less than three per cent of its body mass. Within an hour Laurel will fit the radio-collar and release the predator. The collar will collect about 2 500 GPS points at pre-scheduled intervals, and drop off automatically within six months. Laurel can also send a signal to the collar to force it to dropoff, if required.

The sophisticated technology makes the collars expensive, around R40 000 each. So far Laurel has managed to collar 11 caracals, but eventually she’d like to track 25 and extend her study area to the whole of the Cape Peninsula, all the way south to Cape Point.

Laurel studied mountain lions and bob-cats in the Santa Monica Mountains that surround Los Angeles for eight years. Her research there was instrumental in persuading local governments and communities to put measures in place to conserve these predators. The Table Mountain study is supported by SANParks, the Cape Leopard Trust, the University of Cape Town, City of Cape Town, private landowners, and the University of California in Santa Cruz. Park management welcomes this research as a means to inform management decisions.

The caracals represent yet another challenge of managing a national park within a city metropolis. Caracals here are effectively stranded on an ‘island’, cut off by the extensive urban development on the Cape Flats between Table Mountain National Park and the Boland mountains.

“For probably 20 years now this population has been isolated,” Laurel explained. “We expect to find a decrease in genetic variation, but we will only know for sure once we’ve done the tests.” In-breeding could eventually make the caracals more susceptible to disease or it could make it difficult for them to survive environmental change. “Wildlife needs natural corridors in urban areas such as Cape Town, so animals have a safe way to find new habitat and to enable the overall genetic health to be maintained.”

The stakes are high. The caracals are a symbol of the peninsula’s impressive beauty and its wild animals. Two hundred years ago lions and leopards used to roam Table Mountain, but colonial hunters quickly exterminated them. Now the caracal is the apex predator. Losing the last of its predators can have far-reaching consequences on eco-system balances in an urban national park such as Table Mountain National Park.