I hear the Land Cruiser engine outside. It’s Quinton, back from his flight. Was he successful, I wonder? He comes in beaming, “I got them all! And you won’t believe where Patch is…” Quinton rushes over to the computer to download the GPS data to take a look at where the young male leopard, M17 “Patch”, has been moving for the past four months. He also downloads the data that he got for F5 “Lizzie” the female leopard, and the male caracal, MC3 “Klonkies”. “Oh my word, come check this out! Look where Klonkies has been cruising!”

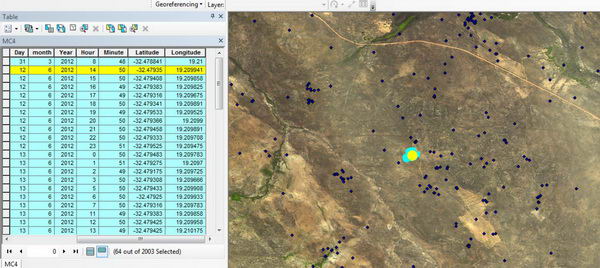

The two most exciting parts of getting the data from the GPS collars is seeing where these cats have been moving and then looking for clusters of points which indicate kill sites. If a cluster shows that the leopard or caracal was in one place for over 24 hours we have found that it means it was feeding on a kill and that its prey was fairly large – dassie or larger. The fun part comes in when we actually go out there and investigate these points, looking for any signs of the remains of the kill.

Satellite map showing caracal GPS points with a cluster highlighted

Leopards eat almost everything. It is common to find their scats near a kill with a hoof inside it, or quills, in the case of when porcupine are eaten. The clues are not always obvious. We look for hair, because the leopards lick and pluck the hair off their prey before they feed; rumen, the vegetarian stomach contents that the leopard finds distasteful; bits of bone, most often the skull, sometimes a piece of leg bone; and scats, from which we can identify the animal that was eaten. Caracals have a different eating style, preferring the meat and leaving most of the skeleton.

Remains of a caracal kill

The information gleaned when kill sites are investigated produces an unbelievably accurate study on the predator’s diet. Quinton used this method in his PhD and a scientific paper in the Journal of Zoology has since been published.

However, leopards and caracal don’t necessarily have their restaurants close to the roads. In fact leopards seem to choose their locations carefully – a spot with shelter and a view to die for (excuse the pun)! This is where the groups participating in the environmental camps come in. Groups are given a kill site’s GPS point, and head off into the veld on this novel kind of treasure hunt, active members in the research process.

During the last three camps, ten kill sites were investigated, and nine of them successful. So what did we find? The young leopard had eaten grey rhebuck, common duiker and even a baboon – unusual for the Cederberg. The caracal on the other hand had eaten grysbok and klipspringer.

Pointing to the remains of a klipspringer – a pile of hair and bones

During their school holidays, the Buys family volunteered their time to help the CLT with some of the more remote kill sites. Here is their story:

During the last weekend of the holidays, Quinton had given us 13 cluster sites to survey in the Cederberg. The cluster data ranged in age from less than a month to several years old, grouped within a 60 square kilometer area near the Matjiesrivier Nature Reserve. Returning to a base camp on a nearby farm each night, we spent 4 days hiking and managed to get to 10 clusters.

The going was tough in this stony region - leopards don’t stick to footpaths and vehicle trails!

Rough hiking in the Cederberg Karoo

Most clusters were typical: overhangs, caves and near water; except one that was on the apex of a mountain. Some clusters remain a mystery – generating no prey or scat evidence. We could only speculate why the leopard paused here – perhaps a date, but more likely crows and jackal picked the spot clean.

Prey samples and scat were collected and returned to CLT for further analysis, but obvious remains included dassie, porcupine, what might be large bird, some small antelope (and also some livestock). We’re especially looking forward to hearing about the identity of “our” mystery skull.

We can certainly recommend cluster hunting as a great volunteer activity that also made much of what we’d read about the leopard so much more real.

Thank you to all these groups who put such enthusiastic effort into helping the CLT gather data for this revealing research.

By Elizabeth Martins, Education and Outreach Coordinator